One way to discover outdoor lifestyles in our Solar System is to look into the atmospheres of distant planets, looking for gases that residing organisms can produce. An organization of scientists thinks we should search for two gases in particular: carbon dioxide and methane.

Most astronomers advise seeking out oxygen as a sign of extraterrestrial life. Oxygen is abundant in Earth’s surroundings because numerous vegetation and other organisms continuously pump out the gasoline. Without lifestyles on Earth, oxygen would ultimately disappear.

But in a new study in Science Advances, scientists recommend oxygen won’t be the first-rate goal because gas didn’t constantly exist in large quantities here on Earth — even if lifestyles became present. Billions of years ago, the Earth’s surroundings had exclusive combos of gases, including carbon dioxide and methane, that only existed together due to the rudimentary existence on Earth’s surface. According to the have look, carbon dioxide and methane react with one other, causing the methane to ultimately disappear unless some organisms keep pumping greater methane into the surroundings.

Finding the one’s gases collectively on another planet isn’t always a clincher. Methane can be produced by expanding procedures, not simply through dwelling organisms. But the authors say they calculated the possibilities of an ecosystem having the two gases with no lifestyles on the floor, and the chances are pretty slim. “You could make a bit of methane without lifestyles,” study writer Joshua Krissansen-Totton, an exoplanet expert at the University of Washington, tells The Verge. “But to get several methanes in the atmosphere, it’s pretty tough to explain for without life.”

Read More Article:

- Coach enjoys the suite life in Pyongyang

- Automobile Publication – November 21 to twenty-five, 2016

- How to move Coachella 2018 on iPhone, iPad, Apple TV & Mac

- So, It’s Pretty Much Confirmed That ‘Dance Moms‘

- How to Survive the Longest Flight in the World

Astronomers have long debated the first-rate ways to search for lifestyles in some distance-off worlds. Some have advised analyzing the light meditated off a planet to see if there are capabilities at the surface that seem like vegetation. Others have argued that we should search for how gases exchange in a planet’s ecosystem. Earth’s carbon dioxide is going up and down in the 12 months while vegetation in the Northern hemisphere dies off within the fall, after which it grows once more in the spring. A comparable seasonal cycle could be going on elsewhere.

Looking for oxygen has usually been the biggest target, although. But even oxygen has its issues: some fashions show that oxygen masses can land in an atmosphere without a lifestyle. That’s why astronomers have recommended searching out oxygen and other gases that “don’t belong” collectively. These gases could chemically react with oxygen and make the gasoline leave. So they’re a sturdy indicator that something — like plants — is retaining the oxygen around.

Our planet is a great example of how this works: oxygen shouldn’t survive with all the methane in our atmosphere, nor should it coexist with nitrogen and our huge liquid oceans. But timber, vegetation, or even plankton within the sea keep replenishing oxygen in our atmosphere; without it, we wouldn’t be around.

Krissansen-Totton and his group desired to understand if oxygen had constantly been our planet’s great signal of life. “If you’re an alien searching out life on Earth, it’d be pronounced now because there’s all this oxygen,” he says. “But might you be able to discover lifestyles at earlier instances in Earth’s records?” The solution: maybe not. There has been no oxygen in the air for the first half of the planet’s history. And for the maximum of the second half, the tiers of the gas were shallow. That’s because it took about one thousand million years for life to start generating oxygen after the primary residing organisms emerged, and it took many hundreds of thousands of years after that for Earth to have an oxygen-rich ecosystem.

The researchers put together their nice estimates of what has been in Earth’s environment because that planet was first shaped four.5 billion years ago. They determined that our world still had four incompatible gases within the first half of the Earth’s life: carbon dioxide, methane, nitrogen, and water. So they advocate seeking out carbon dioxide and methane on different planets; the two gases are simpler to detect than the others. “But in case you find all 4, that’s remarkable,” says Kristiansen-Totton.

Sara Seager, a planetary scientist at MIT who was no longer concerned about this take a look at, says the technique could make paintings. “It’s top-notch to look the … Debate continues with new ideas,” she says. But it’s usually possible that further on, scientists may come up with different eventualities to explain a pairing of carbon dioxide and methane, Seager tells The Verge. “This is regular and wholesome in technology, but in some cases, troubles are not resolved for a long-term or ever,” she says.

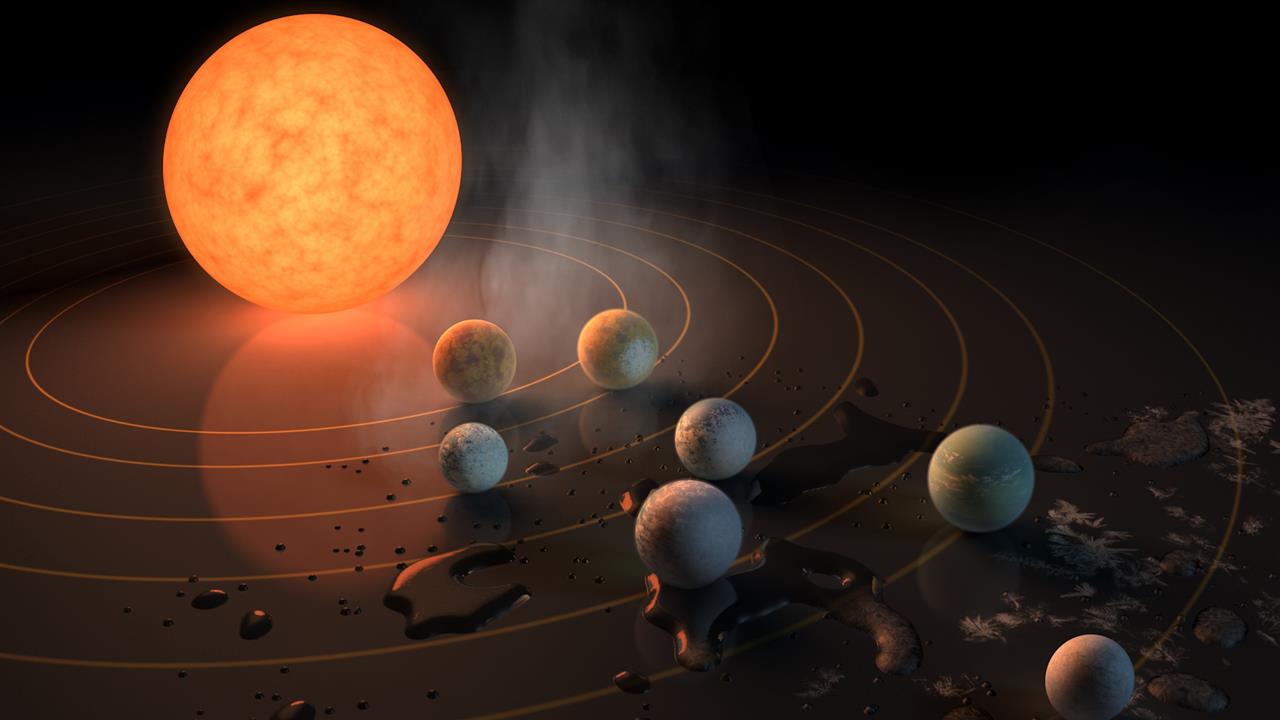

And even though astronomers observed those gases on another world, the planet would need to be small and rocky like Earth, in addition to the proper distance far from its superstar so that liquid water could exist. But we may be choosing up planets like this quickly. NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope is launching next year, and it will be attempting to find unique gases inside the atmospheres of planets. If it does find this combo, even more, effective telescopes in the future may want to observe up and notice if there are extra incompatible gases or liquid water oceans on those worlds.